After World War II, Pablo Picasso chose to live and work on the French Riviera. His strong attachment to the Mediterranean brought him in turn to Antibes and, before Cannes and Mougins, to Vallauris, where he stayed from 1948 to 1955.

Installed in his workshop in Fournas, a former perfume factory, he worked intensely, producing numerous works. works and experiments with a new technique for him: ceramics which particularly caught his attention and which undoubtedly motivated his installation in Vallauris, a city known for its pottery industry.

These are thousands of objects that Picasso will create in the Madoura ceramic workshop, recently directed by Georges and Suzanne Ramié. Plates, dishes, vases, pitchers and other earthenware were painted and decorated with enamels and metal oxides which, by their nature and to the artist’s delight, always mortgaged the final result. But the same objects, taken from the potter’s wheel, could also be transformed.

A few skillfully produced twists metamorphosed them into animal or female nude, faun or tanagra.

If Picasso’s stay in Vallauris remains undoubtedly marked by this prolific ceramic creation, the artist did not forsake the usual techniques such as linoleum engraving or sculpture, the execution principle of which he also revolutionized by integrating recovered objects. (La Chèvre, La femme à la stroller, La Guenon et son petit …) or painting which then begins an explicit dialogue with the works of the great masters (Portrait of a painter after Le Greco, Les Demoiselles au bord of the Seine, after Courbet). But in this post-war period, Picasso’s art also gave way to certain episodes of contemporary history. Massacre in Korea, The Charnier and the famous Portrait of Stalin bear witness to the political commitment of the artist who, despite his recent membership in the Communist Party, continues his questioning of the form and works for its transformation without in any way subscribing to the precepts. of socialist realism.

The terrible developments of recent history are therefore not absent in Picasso’s work, but they are not explicitly mentioned. There are only indications that the precarious times that the world lived through remain present in his work: dislocated objects that can be seen in the many still lifes of this period, human or animal skulls, lamps diffusing a pale light that frames severely the whole.

The abrupt shapes that Picasso gives to objects, the shades of gray to which he limits his palette are, without a doubt, the elements that make the artist’s statement understandable: “A saucepan can also cry!” Anything can scream! “. The work that Picasso produced during the seven years he lived in Vallauris is also rich in what he lived there.

Françoise Gilot, his companion at the time, as well as Claude and Paloma, the couple’s children, are frequently represented in his painting. They go about their business or appear frontally on the canvas. The Mediterranean landscape, the town of Vallauris itself, with the black smoke from the ovens during cooking, are also the themes treated by the artist.

Like the shadow created by the city smoke appears, in certain representations of female nudes (L’Ombre, L’ombre sur la femme, both of December 1953), that of the man on the elongated body of the woman, even though the relations of Pablo and Françoise are experiencing a serious deterioration. As soon as he met Jacqueline Roche – a young girl who would become his second wife – the painter made room for her in his paintings.

This was the time when Vallauris experienced great excitement. Indeed, the presence of Picasso is at the origin of a true artistic emulation: the painters and sculptors Victor Brauner, Marc Chagall, Edouard Pignon, Ozenfant, Prinner … come to work in the ceramic workshops.

WAR AND PEACE

It was in 1952, in his studio at Fournas in Vallauris, that Picasso painted a very large painting – War and Peace. Dealing with a subject which, although directly linked to this post-war era and to the many international appeals for world peace, this work retains an undeniably allegorical dimension. Preceded by some 300 preparatory drawings made in the previous months, it required numerous hardboard panels which were erected vertically on a specially designed wooden structure.

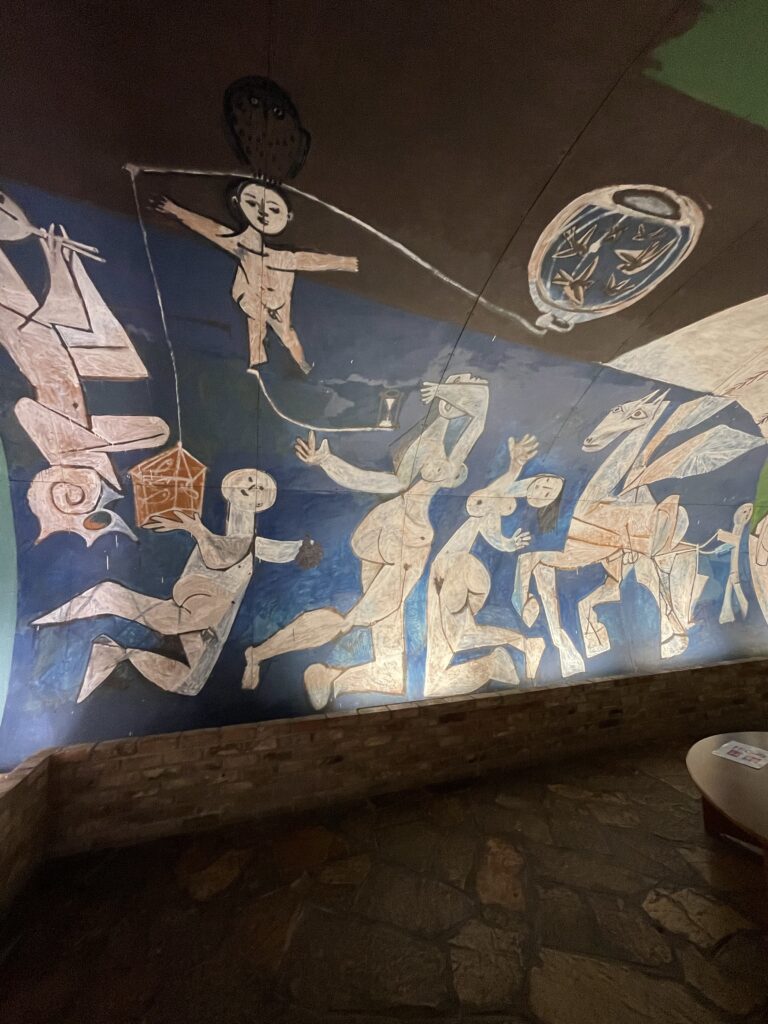

THE WAR

Picasso began with La Guerre. A hearse drawn by war horses, shelled and harnessed, is led by a horned being, armed with a bloodied cutlass. He wears a sort of basket on his back where human skulls are piled up. Other figures appear in Chinese shadow in the background, in the center of the painting. Theirattitude is threatening like the first figure evoked. The three horses which pull the unstable and chaotic catafalque, trample on an open book, finishing the work of destruction which the devouring flames have begun. The book, trampled here, evokes the bias of any dictatorship in the face of culture, generally considered dangerous and subversive.

On the same plane, two painted hands appear in a sort of black hole. They may want to echo those found on the wall of certain prehistoric caves, in particular that of Lascaux, then discovered only a few years ago. In stark contrast to the violent colors surrounding the sinister team, the blue background where the peace fighter appears is calm and soothing, like the latter. Naked, equipped with a spear which serves as a support for the scales of justice, he protects himself with a simple shield on which the artist has drawn a dove, a well-known symbol of peace.

The man seems to fearlessly confront the figures of savagery that rush towards him. On the white shield, as if in filigree behind the dove, a portrait is visible, also of serene beauty. It is that of the artist’s companion, Françoise Gilot. On the other hand, at practically the same height, a rounded white cup lets out strange black shapes, fitted with pliers or prickles. They could evoke the research carried out at the time by the great powers to acquire bacteriological weapons.

THE PEACE

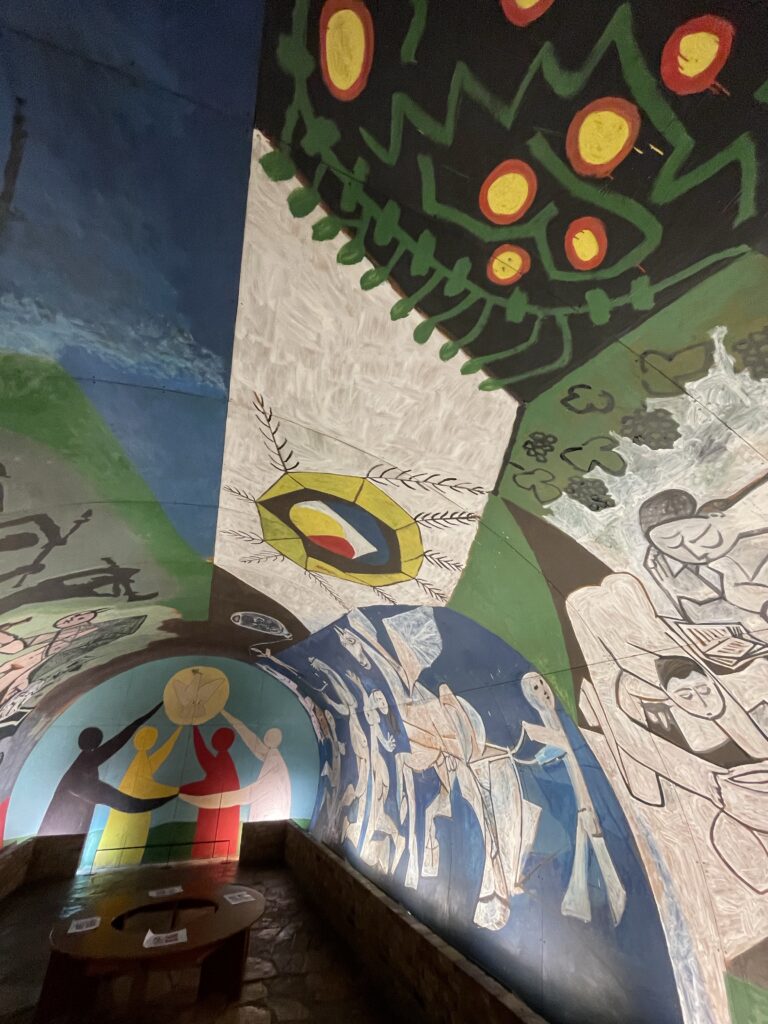

On the opposite wall, Picasso painted La Paix. The whole is read from right to left. The first scene consists of four characters who, in a garden of soft and relaxing colors, engage in peaceful activities. A woman, while reading, breastfeeds her child, under an abundant trellis, a solar sea urchin with abundant and colorful radiations and a tree with luminous fruits. To the rich and generous symbol of motherhood is added that of liberating culture, undermined in the opposite panel of The War.

In a large section of blue color which occupies a large part of the wall, several scenes coexist, all imbued with exuberant joy. A white horse pulls a harrow held by a child who works this azure blue field whose gaze is directed towards the preceding group, another image of fertility. The animal is winged like those that appear in Greek mythology. Keenly appreciated by Picasso, the figure of the Centaur appears regularly in paintings from this period. The diaule-playing faun we see in the work, on the far left of the panel, is also often summoned. It is to the sound of his music that the two naked women dance in the center.

They are accompanied in their development by two other children whose agile and light play shows a certain playfulness. The birds in the jar and the fish in the cage evoke the amused reversal of the elements which, in this enchanting Edenic setting, here in no way bear curses. Even the owl – the usual figure of the dark and deep night – perched on the head of the balancing child, cannot fulfill its usually evil role. She finds a kind of positive counterpart in the shapes of the bunch of grapes the other child is holding in his left hand.

Finally, other interesting clues, the little hourglass at the end of the white support, balanced on the woman’s finger, relays the image of time visible in the spiral of the shell on which the musician sits. Linear, precarious and limited, the time of men thus seems, through this communicative joie de vivre, to be inscribed in eternity.